All Those Memories Gather ‘Round Her

By Ria Nicholas

West Virginia is, just as they say, almost heaven. A playground for the outdoor enthusiast, it offers hiking, biking, white-water rafting, ATV trails, and endless adventure. All this can be had against a backdrop of jaw-dropping scenery: Blue Ridge Mountains! And holed up in the simple accommodations of the little town of Matewan, no one today would guess at the decades of violent struggle that played out in these parts.

But, life is old there – older than the trees. So, while your socks are drying and you’re airing out your boots, take a moment to nose around town, and discover for yourself the dark and dusty history painted on the sky!

Introduction

Matewan lies on the banks of the Tug Fork of the Big Sandy, the meandering river that separates West Virginia from Kentucky but was unsuccessful in separating the legendary, though very real, feuding Hatfields and McCoys.

Significantly the area around Matewan also served as the setting for the West Virginia Mine Wars, a series of confrontations which comprised the single largest insurrection in U.S. history, outside of the Civil War.

It was a pivotal event that determined the course of the development of labor and industry in America. And it presented a tale so action-packed and dramatic that it became the subject of a 1987 movie by the same name.

(The movie “Matewan” was filmed in the nearby town of Thurmond, WV. Because Thurmond was a virtual ghost town by the 1950s – today, it has a population of 5 – it still looked very much like it did in the 1920s. And with no one there to interfere with filming, it made the perfect movie set.)

Owe Your Soul to the Company Store

Although coal was discovered in the area in 1742, West Virginia’s southern coal fields weren’t developed until around 1870, with the onset of the Industrial Revolution. Since the locations of coal mines were, at the time, mostly remote and uninhabited, coal companies built entire towns to service their miners: a company store, churches, schools and recreational facilities, and provided housing (and collected rent).

Miners often needed advances on wages not yet earned, to cover rent. But, for the sake of safety and convenience, coal companies generally didn’t keep large sums of cash on hand. Instead, they often paid miners such advances in ‘scrip.’ Scrip was the coal company’s own currency and was, therefore, only valid at the company store and at other company holdings.

While this paternal approach sounds somewhat idyllic – almost like a contemporary planned community – it frequently led to abuses. As a practical matter, some miners were never able to dig out from under debt, and scrip became their permanent currency. Not surprisingly, many miners felt themselves indentured servants of their mine company employer.

You load 16 tons, what do you get?

—Merle travis, lyricist

The West Virginia Mine Wars Museum, located on the ground floor of the Matewan National Bank at 401 Mate Street, Matewan, WV houses displays and artifacts representing West Virginia’s mining history, the Matewan Massacre, and the Battle of Blair Mountain.

For those who want to dive deeper into this fascinating episode in U.S. history, follow West Virginia’s “Coal Heritage Trail.” You will find additional information and several itineraries on their site.

Additionally, working conditions at the mines were appalling. Hours were long. The work was backbreaking, and unlike today, there were no safety regulations to protect the miners. The mine operators provided little, if any, medical care, and deaths – from accidents and black lung disease – occurred with frightening regularity.

Early Attempts at Unionizing

In the late-1800s, miners began attempts to level the playing field by unionizing, and in 1890, the United Mine Workers union was founded. Mine operators, however, responded by firing union members and blacklisting them from employment at other mines. Because these miners lived in company-owned housing, they were also promptly evicted and often had to resort to moving their families into tents.

Mine operators employed another tactic in undermining attempts to unionize. They often hired 1/3 Anglo American, 1/3 African American, and 1/3 immigrant (Scotch-Irish, Italian or East European) labor, believing that these groups would be too suspicious and distrustful of each other to find common ground.

However, attempts at unionizing and conflicts between miners and company owners continued for decades and escalated into the first workers’ strike in 1912 – 1913. Miners demanded better working conditions, pay commensurate with the inherent dangers, the right to be paid in legal tender, an end to child labor, and recognition of the United Mine Workers (UMW) union.

Enter Baldwin-Felts

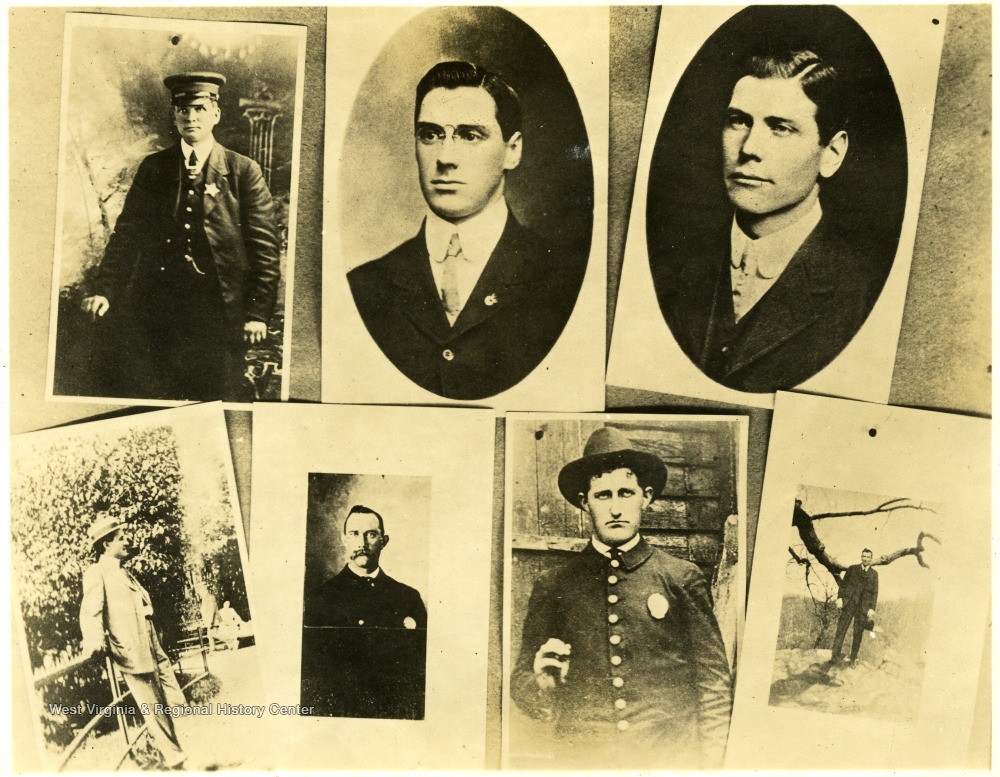

The mining companies refused to meet the workers’ demands. Instead, they hired the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency to guard the mines and break up strikes.

The Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency had been founded in the early 1890s to investigate train wrecks, robberies, and thefts. By the 1910s, the incidents of railroad crimes had decreased, and Baldwin-Felts hired out as private security forces – some might say ‘thugs’ – for mining companies. Law enforcement at the mines, like everything else in the company town, was under the control of the mine company. Using Baldwin-Felts agents, mine operators met strikes, and even attempts to unionize, with force.

The Matewan Massacre

The Coal House Museum in Williamson, Mingo County. Built in 1933, it was constructed using coal masonry. Image courtesy Badagnani, Creative Commons.

The most infamous of the confrontations between Baldwin-Felts agents and miners occurred in Matewan, West Virginia on May 19, 1920. Miners there had been attempting to unionize, and Albert Felts had previously unsuccessfully tried to bribe Mayor Cabell Testerman to place machine guns on roofs throughout the town.

On this date, twelve Baldwin-Felts agents evicted a woman and her children at gunpoint while her husband was away. They threw the family’s belongings out in the rain. Miners who witnessed the event were rightfully indignant.

Two typical West Virginia coal mining families. Anglo-American, African-American, and immigrant families were kept segregated in coal camps.

Unbeknown to the agents, armed miners were stationed in windows, doorways, and on rooftops throughout town. As the agents went to the train station to leave town, Police Chief Sid Hatfied* and several deputized miners attempted to arrest them. Albert Felts responded with an arrest warrant of his own – this one for Chief Hatfield. Someone alerted Mayor Testerman to the stalemate. He took one look at the Baldwin-Felts warrant and declared that “this is a bogus warrant.”

*Sid Hatfield was a distant relative of the Hatfield clan, infamous for the Hatfield and McCoy Feud.

With those words, a gunfight erupted. No one knows for certain who fired first, but Chief Hatfield shot Albert Felts. When the smoke lifted, the exchange had left three miners and seven Baldwin-Felts agents dead. Mayor Testerman and Albert and Lee Felts were among the dead.

The gunfight became known as the Matewan Massacre and symbolized a triumph for the heretofore demoralized mine workers. The union minors immediately elevated Sid Hatfield to hero status. However, tensions between miners and coal companies continued to escalate in the aftermath of the Matewan Massacre.

An Assassination

The 1921 murder trial of Sid Hatfield and his interviews with reporters shone a national spotlight on the plight of the miners. Hatfield was acquitted by an impartial jury. Still, 80% of mine companies reopened with replacement miners who signed “yellow dog” contracts – contracts in which the minors agreed not to join a union. Growing conflict between union and non-union miners was quelled by the imposition of martial law.

On August 1st of that year, Hatfield traveled to the McDowell County courthouse to stand trial, accused of having dynamited a structure used for loading coal. As he walked up the courthouse steps, accompanied by his friend Ed Chambers and their wives, several Baldwin-Felts agents standing at the top of the stairs fired at them. Hatfield and Chambers were killed, and their bodies were shipped back to Matewan.

The Battle of Blair Mountain

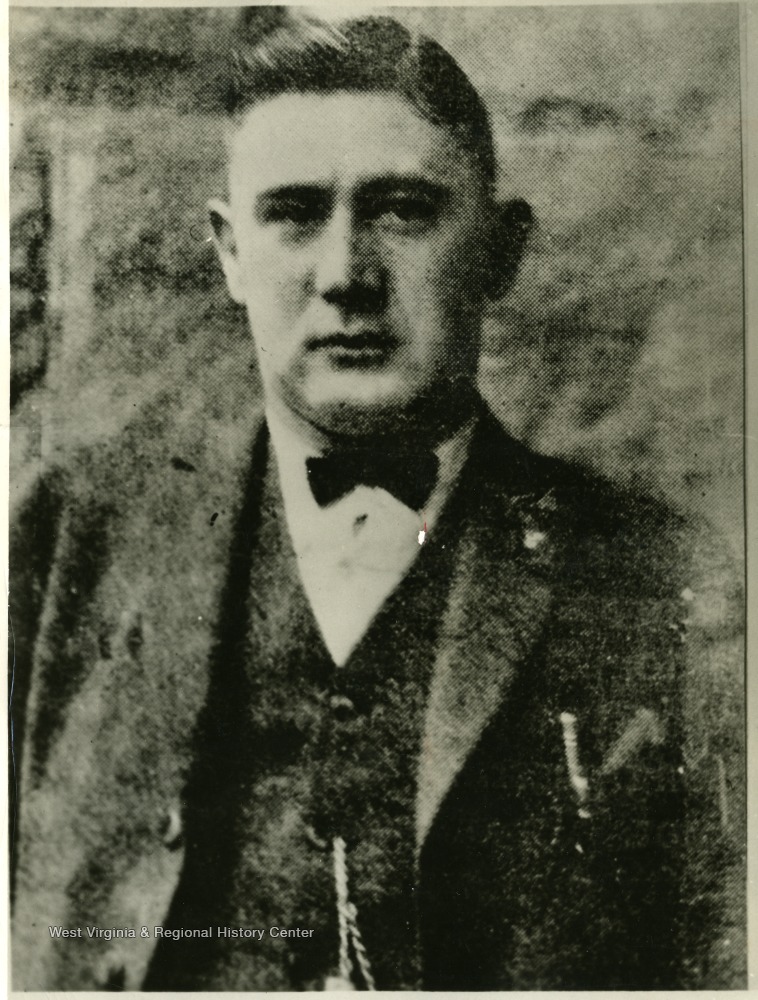

Sheriff Don Chafin

The assassination of Sid Hatfield (and the absence of any legal action against the assassins) ignited the Battle of Blair Mountain, in which 7,000 armed miners marched on Logan County. Meanwhile, the Logan County Coal Operators Association assembled a private armed force of nearly 2,000 men, lead by Sheriff Don Chafin.

Although Chafin’s men were outnumbered, they had better weapons, including private planes hired to drop surplus explosives and poison gas bombs left over from WWI on the unsuspecting miners. Sporadic gun battles continued until September 2nd, when Federal troops arrived, putting an end to the conflict.

State Police and mine guards on Blair Mountain

Up to 30 deaths were reported on Chafin’s side. Between 50 and 100 deaths were reported on the miners’ side. In the aftermath of the Battle, 985 miners were indicted for murder, conspiracy, accessory to murder, and treason. Many of those received prison sentences.

While the miners lost the Battle of Blair Mountain, they ultimately won the Mine Wars. The Battle raised awareness of the dangerous conditions in the West Virginia coal fields, changed union tactics, ushered in safety regulations, and ultimately led to the establishment of the AFL (American Federation of Labor) and CIO (Congress of Industrial Organizations).

Today, the Blair Mountain Battlefield is on the National Register of Historic Places.