Dirty Dealings On Display at the East Texas Oil Museum In Kilgore

By Ria Nicholas

Most folks outside of Texas have never heard of the little town of Kilgore. But, in fact, it lies at the epicenter of a series of discoveries and deals that rocked our history and culture – almost to the core, so to speak. And the whole wild, down-and-dirty drama is preserved in an unlikely building on the campus of Kilgore College, known as the East Texas Oil Museum.

But don’t let the name “East Texas Oil Museum” fool you! If you long to stand in front of a display of drill bits and read dull, technical museum labels, this museum is NOT for you. The East Texas Oil Museum is nothing – and I mean absolutely NOTHING – like that! Instead, it transports visitors to another decade and immerses them in the day-to-day details of life in an oil boom town.

(Click on the link to view the video):

and is an ideal place to show your children or grandchildren what life was like in the not-so-distant past.

Brief Background: The Beginning

Oil madness had started thirty years earlier, in 1901, with Spindletop, the iconic blowout of black gold near Beaumont, Texas, 185 miles to the South. There had been other wells, of course, starting with one drilled as early as 1859 in northwestern Pennsylvania. But at that time, oil was used primarily in kerosene lamps and as an industrial lubricant. Nothing thus far had compared with Spindletop!

Sign up for our newsletter. It’s free:

Interest in the Spindletop field began with self-taught geologist, Patillo Higgins, who reasoned that petroleum should be lurking under the salt dome there. Though Higgins’ theory was initially met with skepticism, the 150-foot-high geyser of crude that later erupted from the newly-drilled wellbore vindicated him. Not only did Spindletop belch up an astonishing 100,000 barrels of oil per day, it attracted a throng of wildcatters and investors to East Texas.

East Texas Oil Museum; photo by Ria Nicholas

At around this same time, the nascent automotive and oil industries began their symbiotic alliance. Details surrounding the “who, what, and when” of automobile invention are topics for another day. But Henry Ford’s 1913 development of a moving assembly line finally allowed him to mass-produce his American classic, the Model T. The internal combustion engine now became a major factor in fueling the demand for oil.

Of Schemes, Scams, and Scandals

Among the speculators drawn to East Texas by the young but growing petroleum industry, was a colorful character with the equally colorful name Columbus Marion “Dad” Joiner. He arrived at what would become known as the East Texas Oil Field in rural Rusk County in 1926 and began spudding wells just after the onset of the Great Depression.

Rural East Texas had been largely bypassed by the economic euphoria of the Roaring Twenties. Life was simple here. Conservative values dominated, and under the encouraging rhetoric of the Hoover Administration, locals perceived the Stock Market Crash of October 1929 as a problem constrained to wealthy Wall Street gamblers. Here, on the other hand, was an opportunity to bootstrap substantial material gain through wholesome hard work. For impoverished rural East Texans, oil exploration presented, perhaps, their one and only chance for a better life. The pump was primed – if you’ll pardon the pun – for wild speculation and exploitation.

The U.S. stock market crash and the discovery of oil in East Texas were major headlines of the day!

Photo by Ria Nicholas.

In an apparent scheme to sell worthless mineral leases to the naively hopeful natives – especially to widows – “Dad” Joiner secured a bogus geological report purporting to show the existence of local oil deposits. He also asserted that major oil companies had begun to invest. To cloak his dubious claims in an aura of truth, he commenced a lackluster show of successive drilling attempts on land belonging to the widow Daisy Bradford. Through his personality and charm, “Daddy” Joiner was able to generate great enthusiasm and to sell more than 100% of several oil leases.

Some historians reason that Joiner’s strategy depended on drilling dry holes. In such events, the loss of investment money could be chalked up to the luck of the draw. Investors would simply have to take their lumps. With nothing to cash in on, they weren’t likely to discover the mathematical impossibility that they were one of six or more owners of “quarter shares” in a mineral lease.

Third from the right is Haroldson Lafayette (H.L.) Hunt in a straw hat.

After abandoning two failed efforts, and after overselling shares to a third well, no one could have been more surprised than Joiner himself, when, on October 3, 1930, he actually struck oil. Success had finally caught up with him: striking oil meant he would now have to answer in court for overselling shares in his ventures.

Enter Another Colorful Character

Joiner’s operation went into voluntary receivership, and he felt motivated to disentangle himself from the legal repercussions of his faulty math. The answer seemed to lie in the sale of his oil interests. The purchaser was Haroldson Lafayette (H.L.) Hunt, a successful businessman and gambler, who had parleyed his winnings at the poker tables of New Orleans into a portfolio of oil well investments.

Although Hunt was broke at the moment, he had accumulated a wealth of experience and savvy. In a smoke-filled Dallas hotel room, Hunt gathered an entourage of financial supporters to front him the money, to spy and report to him on other East Texas drilling efforts, and to isolate “Dad” Joiner from the latest news emerging from the oil field.

Once Hunt received word of the success of the Deep Rock well, only a mile West of Joiner’s discovery well, he negotiated the purchase of Joiner’s rights in the East Texas Oil Field. The price? A million dollars and change – to be paid in installments. As part of the package, Hunt agreed to protect “Daddy” Joiner from his many legal liabilities. Meanwhile, Joiner, who remained ignorant of the fact that Deep Rock had also struck oil, believed in the advantage of his deal. But, alas, the con man had been conned. Joiner had sold his interests to Hunt for a fraction of their actual worth.

At the time of Joiner’s death, some nine years later, his estate was only negligible. By 1957, Hunt*, on the other hand, counted among the nations wealthiest men, and by the time of his death in 1974, his net worth was estimated at $1 billion.

*The Museum, which opened in 1980, was originally funded by Hunt’s Placid Oil Company and furnished by donations of artifacts from community members. Today, the Museum is supported by gifts, grants, and admission fees.

“In terms of extraordinary, independent wealth, there is only one man—H. L. Hunt.”

–J. Paul Getty, Founder of Getty Oil

Petroleum Delirium

As Deep Rock and other nearby wells in East Texas struck oil, it set off the biggest frenzy since the Klondike Gold Rush. Wildcatters poured in from everywhere, farmers converted to roughnecks, and the rate of drilling and oil production skyrocketed to over a million barrels a day. It quickly reached the point of saturating the market – and the ground – and plummeting oil prices to 15 cents a barrel.

In 1917, the Texas legislature had declared petroleum pipelines to be common carriers*, and in the ensuing years had tasked the Texas Railroad Commission with regulating oil and gas production. But, even though the Railroad Commission imposed rations at the East Texas Oil Field, it had no power of enforcement. And the local population was in no mood to be denied. Many assumed the oil boom would be short-lived and were desperate to stake their claim.

*A common carrier is an individual or business that regularly transports goods or passengers on regular routes at set rates. Today, common carriers are federally regulated. Utility companies and telecommunications companies also are considered common carriers.

The result was a melee of run-away production. In response to the unapologetic squandering of natural resources in defiance of the Texas Railroad Commission, Governor Ross Sterling took action. He deployed the Texas Rangers and the National Guard to restore order and enforce production limits. Although a federal court overturned Sterling’s right to impose martial law, it became obvious that something had to be done!

“If an inhabitant from Mars were to visit us, he could hardly escape a feeling of bewilderment if not actual dismay at the manner we earthlings carry on this great enterprise, so essential to our convenience and welfare.”

–William Farish, Humble oil

Tax revenue derived from Texas oil production now outstripped taxes generated by “King Cotton.” The roller coaster ups and downs of this unregulated industry disrupted the economy of the entire state. Finally, a special session of the Texas Legislature passed the Connolly Hot Oil* Act of 1935. It essentially authorized Federal enforcement of the Texas Railroad Commission’s directives, which attempted to stabilize oil production.

Contrary to the concerns of wildcatters, the regulation of oil production worked. Oil prices rose and stabilized, and the economy continued to flourish. The rest, as they say, is history.

* Hot Oil is a term for oil illegally produced (and smuggled) above the amount allowed by quotas.

Take a peek inside the barber shop at the East Texas Oil Museum. Photo by Ria Nicholas

Oil, Oil Everywhere . . .

Photo by Ria Nicholas

The population of Kilgore, which had grown from 500 people before the boom to 12,000 by the middle of the decade, settled down as well. Businesses of all kinds benefited, and the standard of living in East Texas improved vastly.

Geologists subsequently determined that the East Texas Oil Field is one immense deposit of oil, one of the largest in America. Since its discovery, it has produced nearly six billion barrels of oil. In fact, the petroleum produced from the East Texas Oil Field significantly contributed to driving the allied military machine during WWII.

Today, oil touches our lives in countless ways. It is, of course, the basis of most of our transportation fuel – of gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel. Oil is necessary to the production of plastics – in countless toys, medical devices, and household items. It is used in asphalt, plexiglass, and solar panels. Oil is present in electronics, textiles, dish washing liquid, and sporting goods. It serves as an additive in many cosmetics and beauty products – and not just as their containers. And, like it or not, it even shows up in our food on occasion, in the preservatives. Lastly, because every silver lining has its dark cloud, it has grown into the dual global burdens of carbon emissions and plastic pollution, challenging the inventiveness and audacity of the next generation.

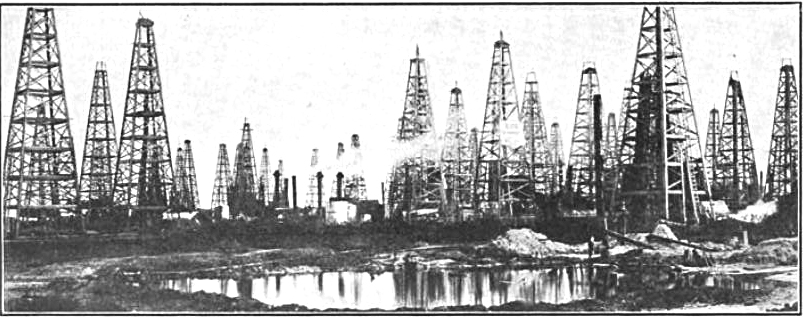

At the height of production, there were 1,100 oil derricks in Kilgore alone.

Sign up for our newsletter. It’s free:

Travel Tips

Location and Hours

Kilgore is located only 30 minutes East of Tyler; 1 hour West of Shreveport; 1 hour, 50 minutes East of Dallas; 1 hour, 50 minutes South of Texarkana; and 3 hours, 10 minutes North of Houston.

You will find the East Texas Oil Museum at 1301 S. Henderson Blvd., Kilgore, TX 75662, on the Kilgore College campus. Free parking is available on Ross Avenue, behind the Museum.

Hours are generally Wednesdays through Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.; however, the last admission is at 4 p.m. (We recommend that you allow at least 1 ½ hours to tour the museum.) Additionally, because the museum is part of Kilgore College, it is closed during Thanksgiving, Winter, Spring, and Easter breaks. (Be sure to check the schedule in advance.) At the time of this writing, adult admission is $10, with discounts for children, seniors and military.

The museum is ADA accessible.

Where To Stay

(Note: we are not receiving any compensation for this recommendation.)

We stayed at the Comfort Suites, just 1 mile from the museum at 1210 Hwy 259 N, Kilgore, TX 75662. The rate was very reasonable, and the room was spotless and contemporary. Of course it had a mini-fridge, microwave, coffee maker and large cable TV. We also appreciated other thoughtful touches, such as the generous number of outlets, including a charging station at the desk. The restroom had a sizeable counter and a gentle nightlight. (No need to flip on a light in the middle of the night and blind yourself.) And there were plenty of towels. Because of COVID, the kitchen was closed, but the hotel provided a brown-bag continental breakfast.

Nearby Attractions

While in Kilgore, we also visited the Texas Broadcast Museum, located at 416 E Main Street. This museum spotlights the people and equipment of broadcasting’s Golden Age and features working television and radio studios and vintage equipment of all sorts – even vintage news trucks! Needless to say, we played here for a couple of hours as well. The Broadcast Museum is open 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Fridays and Saturdays. Adult admission is $6. (We will feature additional information on the Texas Broadcast Museum in a future post.)

Tyler Rose Garden

The Tyler Rose Garden, located at 420 Rose Park Dr, Tyler, TX 75702, is a 30-minute drive west of Kilgore. This 14 acre public park, established in 1952, is the nation’s largest rose garden and boasts more than 38,000 rose bushes, as well as fountains, walking paths, and gazebos. Admission to the Rose Garden is free. Please visit their website for hours, best time to visit, and for information on the Rose Garden Center and on the Rose Museum and Gift Shop.

Texas State Railroad

Seventy-four miles (one and a half hours) southwest of Kilgore, in Palestine [PAL-eh-steen], you can board an historical train for a four-hour round trip through the East Texas Piney Woods. Originally built in 1883 to haul raw materials to a smelter at the state prison in Rusk, the Texas State Railroad now serves as a popular tourist attraction. The Palestine depot is located at 789 Park Rd 70, Palestine, TX 75801. Please check their website for dates, times, details and to book your reservations. While we didn’t swing by the Texas State Railroad on this trip – it doesn’t operate in February – we have ridden the train there before. We have a special place in our hearts for vintage trains and steam locomotives, so of course we loved it. Everyone should experience a vintage steam train ride at some time in their lives.

Please contact us. Our store, Kilgore Mercantile is featured in your downtown photo. Very interested in your mugs.

LikeLiked by 1 person