Please welcome guest writer, Jim Zura. He has spent 30-plus years in broadcasting, beginning as radio personality ‘Jimmy Z’ with M105 Classic Rock in Cleveland, Ohio. After moving to Houston, Texas in 1983, he worked on the air at KILT-FM radio, before his segue into video production. Zura has worked with countless celebrities and has been a location shooter / producer for most major television networks and many corporations. He is the owner and CEO at ZuraProductions.com. —Ria Nicholas

From Morse Code to Social Media – In Just 150 Years!

By Jim Zura

Introduction

It took a quite a while, but the whole story of the evolution of social media can be traced at the Texas Museum of Broadcasting & Communications in Kilgore, Texas.

It wasn’t too long ago that broadcasting was solely the domain of Radio, TV and Cable. Now, thanks to the Internet and social media, you, too, are a broadcaster with worldwide transmission capabilities, right from your home!

Sign up to get more articles. It’s free:

Yes, the Internet is the most prominent means of communication and entertainment today. But what were its primordial origins? And how did it become our daily mainstay? And what exactly is meant by broadcasting, anyway?

‘Broadcasting’ simply refers to a way to transmit our communications from one place or person to another. Stay with me here, because your Internet searches and social media posts directly evolved from a fascinating story that you can trace at the Museum in Kilgore.

Founders Chuck Conrad and Warren Willard, and Operations Manager Dana Pearce, are cordial hosts for this splendid tour through their amazing display of visual and interactive delights representing the progress of radio, television and recording methods since the beginning of media!

Morse Code was developed in the mid-1800s and, for the first time, enabled long-distance communication along the log poles that ran beside railroad lines (and also via flashing lights in maritime applications). This is the first example of “broadcasting”.

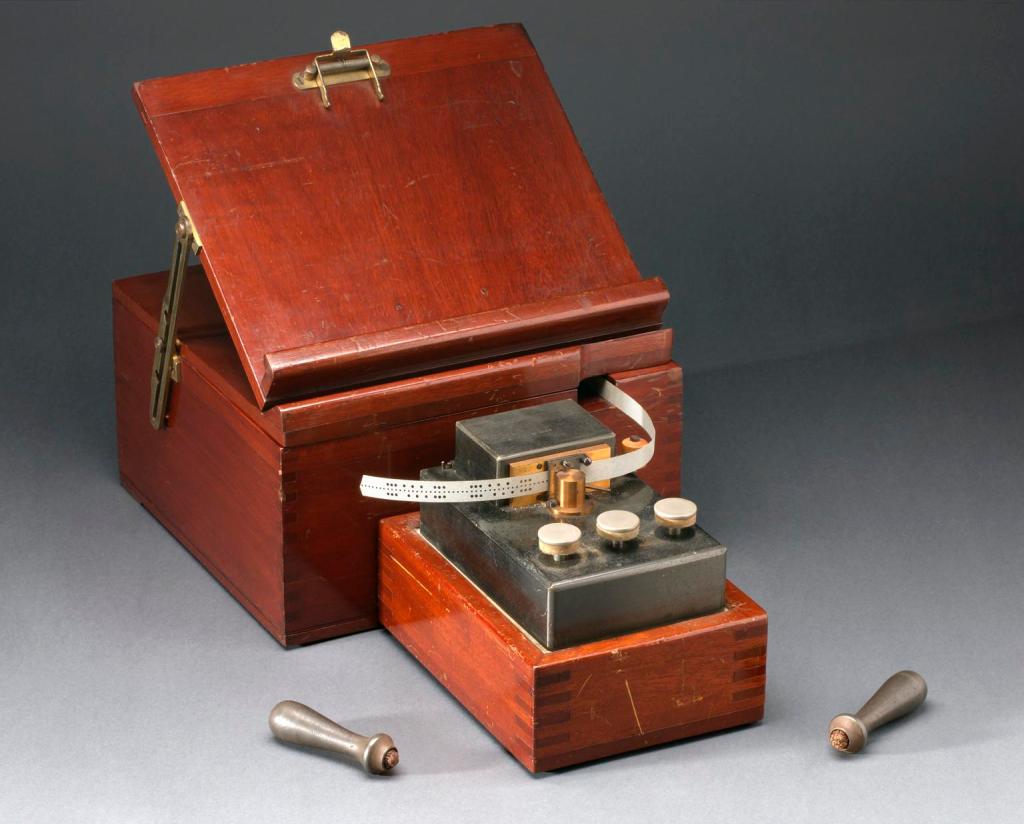

The evolution of recorded media paralleled the evolution of broadcasting. In fact, it was Morse Code that innovated the first recording technology: the Wheatstone Perforator, introduced in 1867. This device created perforations on a paper tape – the first example of “tape recording.”

Click on the link below to view the video:

RECORDED AUDIO: CONSUMER PRODUCTS

Phonographs and Gramophones

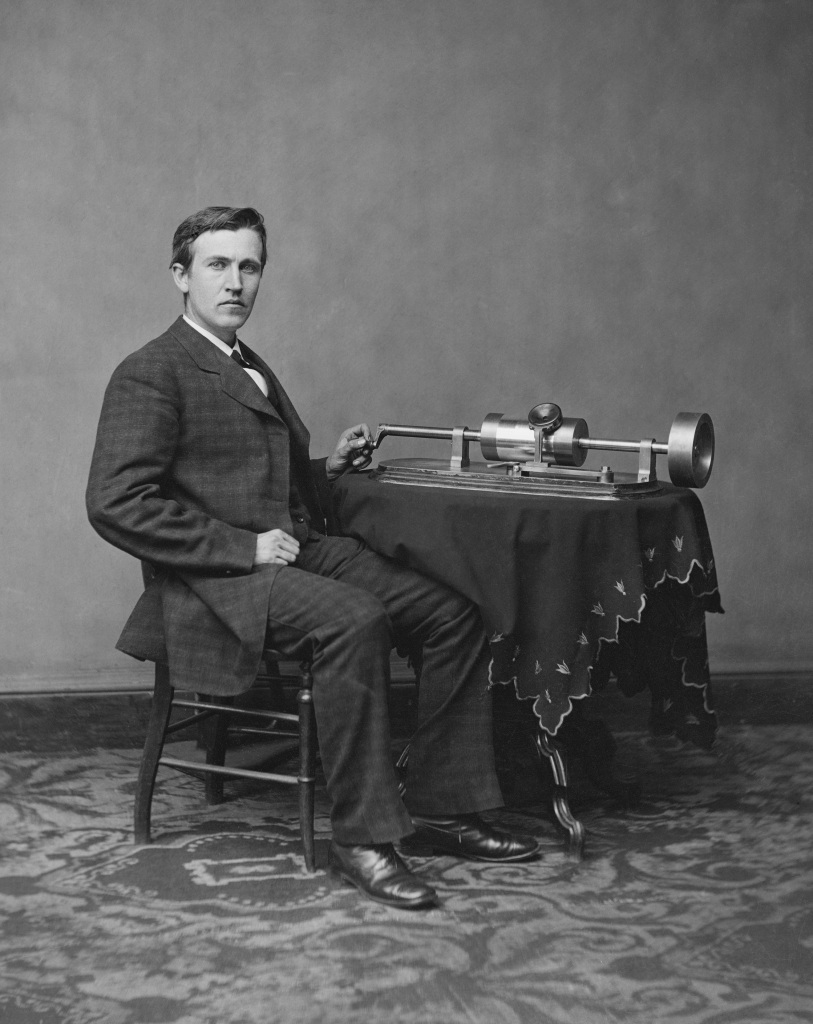

While Thomas Edison is generally credited as the inventor of the phonograph, the perfection of his electric light bulb drew his attention away from this device. Many other innovators picked up the ball and ran with it (too many names and dates for this ‘short’ article).

The original recording devices employed a spinning drum, originally covered with tinfoil, which evolved into hard wax cylinders that could be removed from the device and played back elsewhere. (The original voicemail . . . or file sharing?)

This concept evolved into the flat-disc Gramophone, which could be more easily reproduced. Originally made of brittle Bakelite or shellac, and rotating at 78 RPM (revolutions per minute), vinyl records were becoming popular by the 1930’s. By this time 33 ⅓ RPM, Long Play records allowed for much longer recordings.

Vinyl Records

The 45-RPM “single” record came out in the 1950s and became the standard for radio station playlists and song popularity ratings such as the Billboard charts. All in all, vinyl records had quite a lifespan that lasted well into the 1990s, when the Compact Disc (CD) became the dominant format (although vinyl records have experienced a resurgence in popularity in recent years).

Of course, we can’t forget the evolution of other recorded media in the interim. Up until the mid-1960’s, the only way to listen to music in your car was to turn on the radio. Vinyl records were played on a turntable, where a stylus (needle) tracked through the record. While attempts were made to create a turntable that could be used in a moving car, nothing succeeded in preventing the bumps and vibrations in a car from skipping the stylus.

8-Track

Then came the 8-track tape cartridge. Inside, there was a continuous loop of ¼” audio tape, and it could hold an entire album of recorded music. During that era, factory installed in-the-dashboard 8-track players were standard in higher-end auto models.

Cassette Tape

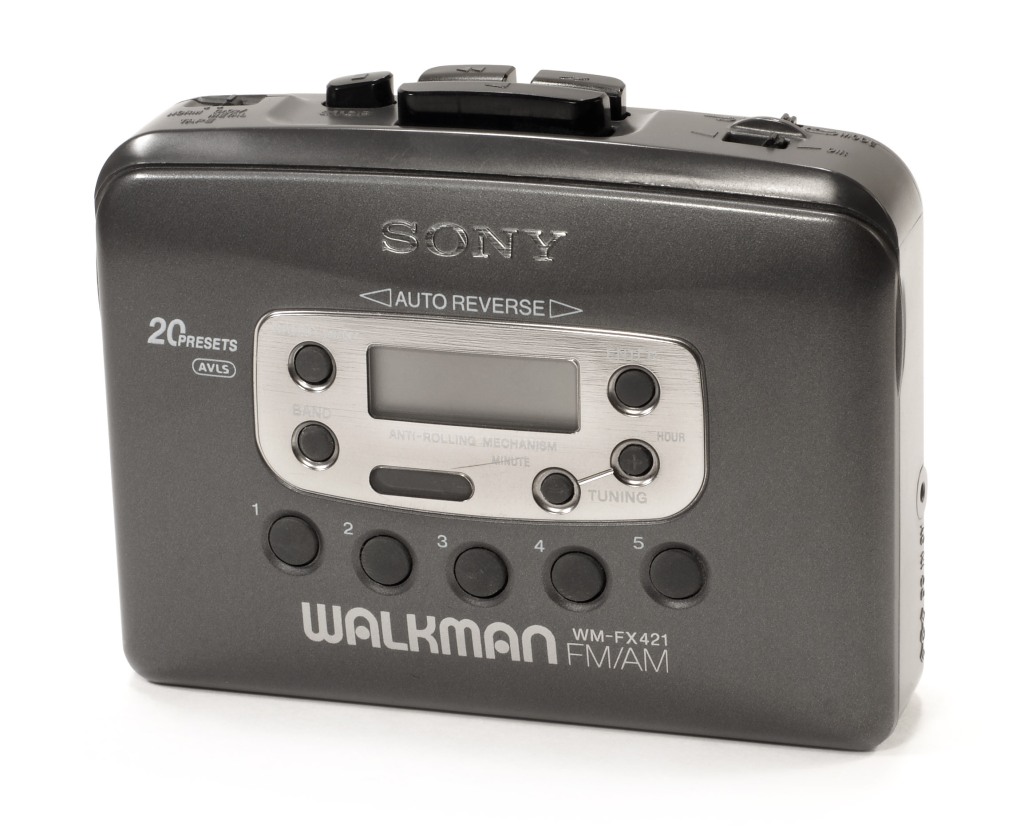

Still, nothing lasts forever. In the early 1960’s the Compact Cassette was developed. It was intended for, and initially used in, dictation machines. At this time, the audio quality of both the tape and playback machines were not suitable for music. With advancements in the quality of those components, the Compact Cassette began overtaking the 8-track in the 1970’s.

With the introduction of the Sony Walkman, a new era of playback portability ushered the Cassette in and the 8-track out. Additionally, users were now able to record their own song choices off of a record player or the radio (or even with live music) – the beginning of Mix Tapes!

CDs

All of these magnetic tape-based media were analog and worked by running linear tape across a playback / record head. Digital audio in the form of the CD spent the early 1980’s achieving critical mass. It was off to a slow start since the original consumer players cost $1,000, and product availability was limited. However, by 1991, CD sales had eclipsed both vinyl records and cassettes.

Sign up to get more articles. It’s free:

Streaming

After a 20-year life span, major retailers like Best Buy and Target began phasing out CD sales in 2018. With iTunes, Beatport, Amazon, eMusic, Spotify and numerous other Internet-based outlets, the way we enjoy music has taken yet another turn. (But to serious music aficionados, it seems crazy that CD’s have become obsolete. Many of the Internet-based music providers apply a good deal of compression to the music, making it inferior to the high dynamic range of the CD.)

RECORDED AUDIO MEDIA: PROFESSIONAL

Reel-to-Reel

So far, our discussion of recorded audio media has focused on consumer-oriented formats. But behind the scenes, another format was at the root of technological improvements in the quality of recordings: the reel-to-reel tape. Originally experimented with in the first part of the 1900s, inherent distortion and inferior fidelity prevented its acceptance – that is, until right after World War II.

When the Allies took over Nazi Germany, they discovered advanced reel-to-reel tape machines in radio stations that applied a new technology (called AC / DC Bias) that greatly improved the quality (and has remained in use ever since).

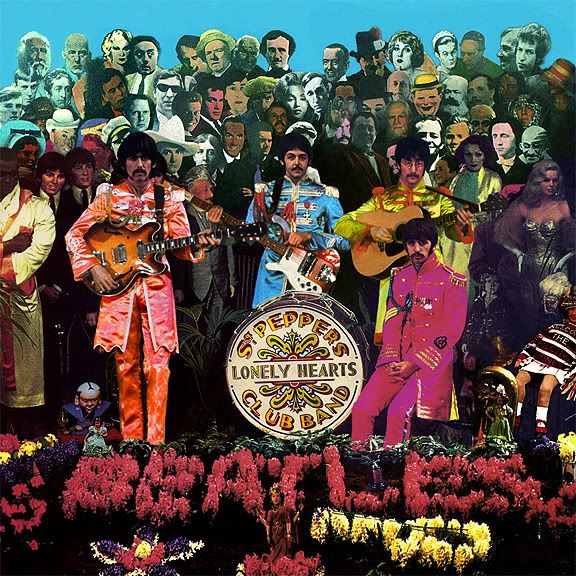

This invention radically changed radio and audio recording techniques. Beginning with single channel ¼” (wide) magnetic tape, it advanced to stereo (two tracks), and by 1967 the Beatles were using four-track reel-to-reel recorders to produce “Sgt. Pepper’s . . . ” By the mid-1970s, two-inch reel-to-reel tape was capable of recording 24 tracks in the studio.

Every radio station had several tape machines for producing commercials and playing recorded programs. The 1/4” tape could easily be edited by accurately cutting it with a razor blade and splicing it with special tape.

Portable machines were popular in schools and for training facilities. Upscale audiophiles made use of ¼” reel-to-reel tape machines for home use, but with limited product availability and expense of the hardware, this format was confined to specific consumers.

Digital Audio Tape

The concept of audio tape took one more step before becoming obsolete. Digital Audio Tape (DAT) was in use professionally in the 1990s but was phased out by 2005. Proponents of this format expected success in the retail consumer market, but it never took off.

BROADCASTING: RADIO

So far, we’ve taken a brief tour of the history of recorded audio media. (Brief??? Believe me, there’s a Universe full of info on this. Just google it.)

By 1900, the entire world was abuzz in technological advancements in the world of electronic communications, giving birth to the telephone (hard-wired) and radio (wireless). By the 1920’s, radio stations had been established in 88 countries!

Radio brought entertainment and news right into people’s homes and cars.

Transistor Radios

I remember being glued to the radio during my childhood in the 1960s, especially after seeing The Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1964. I was addicted to Top-40 Radio. When my older brother went to college, he generously left me his transistor radio. And the transistor radio was the holy grail that propelled popular music into being a predominant force.

Until then, radio listening in the home and car required a very bulky vacuum-tube radio. Huge tube radios only appeared in cars as a pricey option. Transistors replaced bulky vacuum tubes and helped mainstream America access rock-n-roll on the go. By the mid-1960s transistor radios became stock items in cars.

AM Radio

AM or FM? Throughout the 1960s, AM radio was the domain of Top 40. Most automobiles didn’t have FM, and that format was the domain of classical, easy listening and ethnic music.

Then came The Beatles “Sgt. Pepper’s” album. Arguably the first contemporary music Concept Album, it paved the way for many other musical artists, as young people’s listening habits expanded from just buying single records to buying albums. By the late 60s, artists began exploring longer format musical pieces, not just 3-minute singles. AM stations, however, competing to play the “most songs every hour,” stuck with the singles format.

FM Radio

Then, circa 1970, college radio stations began giving young audiences what they wanted, and the Album Oriented Rock format gained ground among radio listeners.

Through the nature of electronics, the FM radio signal is much richer than AM, and since the progressive album rock featured more sophisticated musical arrangements, the demand for FM radios was on!

At the time, FM stations were not very highly rated, because the over-40-crowd audience didn’t consist of regular, loyal listeners. Many radio station owners had both an AM and an FM station. Encouraged by a new wave of knowledgeable DJs just getting out of college and who embraced the Album format, some station managers felt, “Let’s give them a shot. What have we got to lose?” After all, these entry-level radio announcers weren’t demanding much in the way of compensation.

As the 1970s progressed, FM music stations clearly surpassed AM in the ratings. Not just the rock genre, but country, pop, and what was then called the Black / Urban format also joined the fray.

Subscription and Streaming

Other than improvements in quality on both the transmitting and receiving ends, not much really changed until well into the 21st century, when subscription based providers, such as Sirius, and a plethora of Internet based podcasts and streamers came onboard.

RECORDED VIDEO MEDIA: PROFESSIONAL

If radio was great, television was even better. But before we get into the nuts and bolts of how TV was broadcast, let’s take a look at how visual media was recorded in the first place.

Kinescope

Originally, all TV programming was live, since there was not yet a means of recording the television signal. The first method of recording TV was with a Kinescope, which simply amounted to pointing a film camera at a TV monitor. The picture produced was of a very poor quality compared to what we see today.

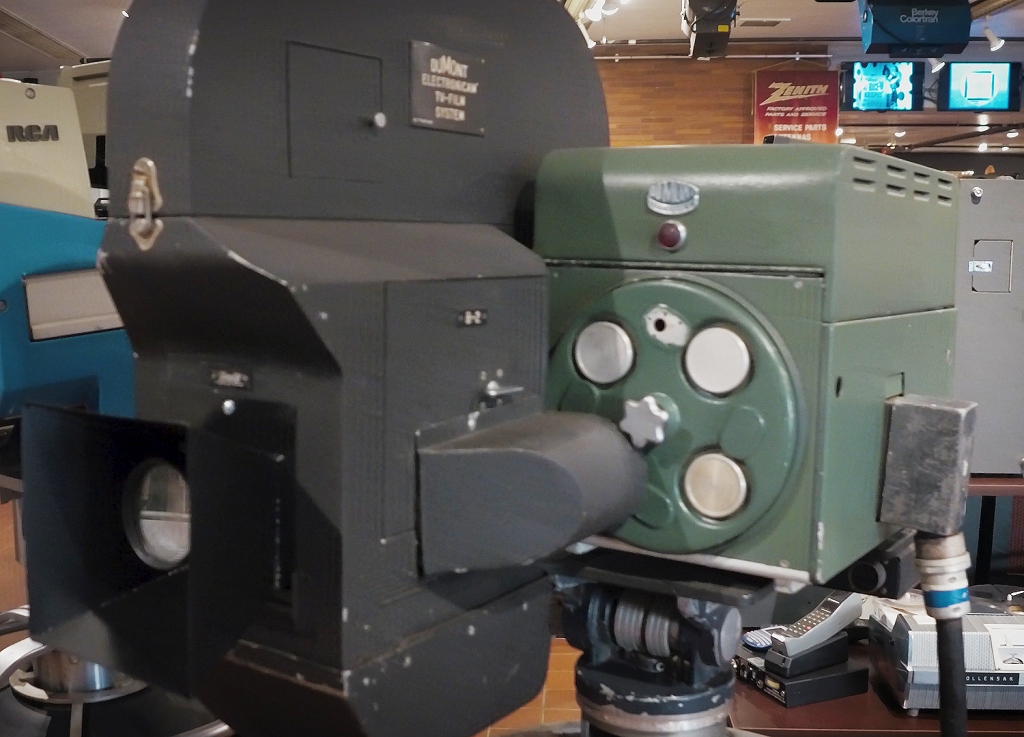

Electronicam

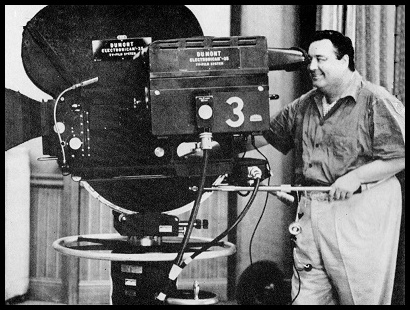

In 1955, the DuMont Television Network developed the Electronicam, a combination live TV camera and conventional movie camera that simultaneously recorded the program on film for later distribution. The “Classic 39” episodes of Jackie Gleason’s “The Honeymooners” utilized this beast!

The Electronicam insured that those TV shows were preserved on pristine high quality film. And, this enabled the concept of reruns. Reversing the process – capturing movie film for TV broadcast – utilized a process called telecine, This special process accounts for the different frame rates: TV in the U.S. is 30 frames per second; movies are 24.

Videotape

The first professional broadcast-quality videotape machines utilized two-inch wide video tape on reels. They were introduced by Ampex in 1956. It took into the 1960s before most local TV stations could afford such technology, but the national TV networks quickly took advantage of finally being able to record and edit quality television shows and re-broadcast them later and again.

Without going into technical detail, a quick laundry list of video tape formats launched from the downsizing of the video reel-to-reel tape format to the One-Inch (tape width), then onto a succession of Videocassette formats.

While there were “portable” one-inch machines, valuable for instant turnaround news-gathering, they were still quite bulky and power hungry. The first truly portable videotape recording format was the Sony ¾” U-matic cassette, with its practical, portable recorders. This format won the hearts of TV news operations and also opened the door for Corporate Videos to flourish.

Sign up to get more articles. It’s free:

Sony Betacam

Then Sony greatly increased the quality of the portable videocassette with the advent of Betacam and its successor BetacamSP. This was clearly the best format, and for many years it was the only format, that the TV networks accepted from us camera folks in the field. (This is not to be confused with the ill-fated Betamax consumer format.)

Digital HD TV

Through the 1980s, tape cassette formats included JVC’s S-VHS, Panasonic’s MII and DVCPro, Sony’s DVCAM and Digital Betacam (and others I won’t bore you with). But this would all go away with the advent and critical mass of High Definition (HD) Television. Prior to HD, the Standard definition resolution was a maximum of 720 by 480 pixels on your television screen. HD increased the resolution to 1920 by 1080 pixels. While there were initially tape-based attempts at recording and editing HD, they didn’t last long since HD is inherently a digital video format, and non-linear editing became the norm.

Many of us with career experience in tape-based formats were initially a bit skeptical: Could we trust that our work was recording on a digital camera card? Gosh, how many times have our computers had issues with “kernel panic”, “not responding” or external devices not being recognized? Well, we all made it through the early years of this century, and now we’ve long been enjoying the incredible advantages of the digital revolution in video.

Shooting on BetacamSP in the old days at a remote travel location often included heading back home on an airplane with several breadbox-sized cartons of tapes, containing a total of several hours of raw footage. And, rather than sending them through the security conveyor belt at the airport, we had to convince the TSA that these magnetic tapes could be destroyed by the scanner. We had to hand the tapes to the agents unscanned (which often proved to be difficult). Today, those hours of footage can be contained on a couple of camera cards that fit into my shirt pocket, and since they’re not magnetic there is no issue with security.

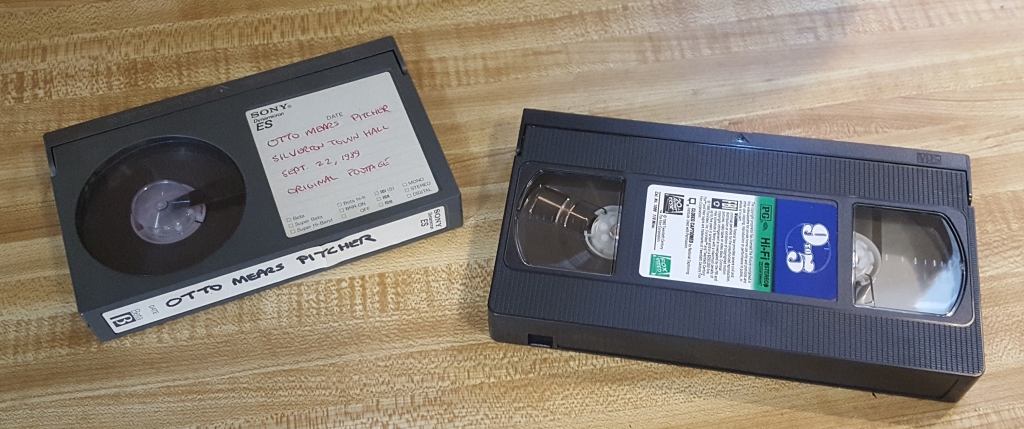

Left: 10 BetaSP field tapes = 5 hours of Standard Definition raw footage. Right: 3 digital camera cards = 5.5 hours of High Definition raw footage.

RECORDED VIDEO MEDIA: CONSUMER

The first consumer-grade videocassette players / recorders were launched in the mid 1970s but were not truly affordable until the early 1980s. This created another industry: movie rentals.

VHS vs. Betamax

The basic “format wars” of that time were between JVC’s VHS (Video Home System) and Sony’s Betamax. Here’s where Sony really miscalculated: At optimum quality, the VHS format provided for recordings of up to two hours. Conversely, at optimum quality, Betamax allowed for only 90 minutes.

Sony (Betamax) somehow missed the fact that the average timing of a Hollywood movie is 96 minutes. Oh, you could double the capacity of the Betamax by selecting the 180 minute option, but that greatly reduced picture quality. Sad, because the video quality of Betamax at its standard speed (90 minutes) was definitely superior to VHS.

GoPro, DJI, etc.

As consumer camcorders became affordable to the average family beginning in the 1990s, more video formats entered the market. As the century turned, as with professional video, consumer video also became exclusively digital, and the SD card has since become the standard media. Formats? Well GoPro, DJI and other manufacturers offer the option of .mov (Apple) and .mp4 (everything else). Most editing software allows either one, or even a mix. (A more technical discussion would include AVI, H.264/265, WMV, FLV and others.)

LaserDisc

In the 1980s the 12-inch LaserDisc attempted to gain a place in the video market. This format provided a much higher quality picture than VHS tapes, and it was also the first example of Interactive Video. The end user could make choices during the program that would affect how the playback would branch to a selection of segments, and would affect the outcome.

This was an advantage for training programs; if the user got a question wrong, it would branch back to a review segment, and also keep a log for the trainer to review strengths and weaknesses. It was also touted as a way for movie directors to create branches based on user input, so the plot could change depending on the users’ choices. Despite these advantages, the cost of the players and disc production never reached critical mass, so they were not affordable for most consumers.

DVDs

It took most of the 1990s for digital video technology and agreement among the highly competitive manufacturers to create a unified format for the Digital Video Disc, which we know as the DVD. Using the same size disc as the already popular audio CD, the DVD could hold just over two hours of high-quality (albeit Standard Definition) video, and featured onscreen menus for interactive user choices.

Blu-ray

The DVD all but completely replaced VHS for video playback and recording. However, the DVD is limited to Standard Definition with a resolution of 720 by 480 pixels on your screen. As this century progressed, High Definition TV became more popular, and it isn’t possible to use the standard DVD format for HDTV. By the second decade of this century the Blu-ray Disc, with the HDTV resolution of 1920 by 1080 pixels, made its way into the consumer marketplace.

While Blu-ray players and movies are still readily available, with ever-increasing internet speeds and high quality streaming services, the age of physical video content is certainly waning.

4K and Beyond

4k video (3840 by 2160 pixels) is already popular in professional use, and as of this writing it is making its way into the consumer market, but content is limited. And, you can actually buy an 8K TV (7680 by 4320) at Best Buy today, but there is currently no practical consumer content available. Technically, there is a 16K (15,360 by 8,640) but that would be reserved for huge commercial display purposes.

Caption. Again, the Texas Museum of Broadcasting has fascinating examples of all of the above (except for 8K & 16K)!

BROADCASTING: TELEVISION

While there were earlier attempts at television broadcast, it wasn’t until after World War II that things really began to get under way. By 1949 there were 98 TV stations in 58 cities in the U.S.

Black & White

As stated earlier, in the beginning, all television was live, since cameras, transmitters and monitors predated the ability to record the TV signal. The development of TV is populated by dozens of inventors and technicians, but perhaps the most prominent were Vladimir Zworykin and Philo Farnsworth, who were embattled in a patent war in the 1930s. The Farnsworth Technology was acquired by RCA, which set the standard of a 525-line black-and-white system in 1941.

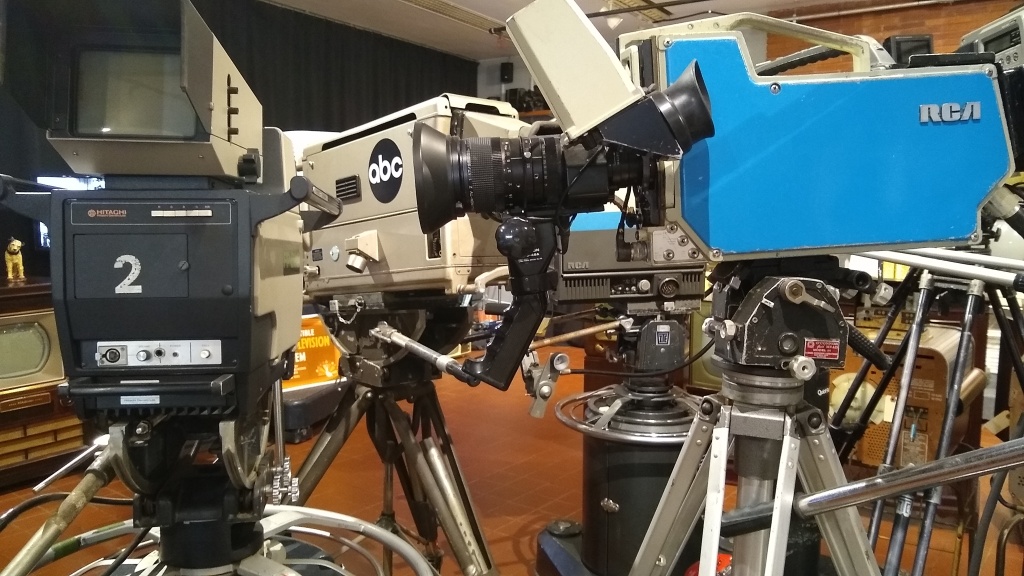

Of course, World War II slowed down the development of consumer entertainment products. In 1949, DuMont Labs debuted its Telecruiser – a mobile TV remote production facility built into a in a Flxible (spelling is correct) bus-based vehicle! The Texas Broadcast Museum acquired the very first one built for KBTV-Channel 8 in Dallas! It is configured for three cameras and was in use until 1972. (It was later owned Tom Potter, a Kilgore oil tycoon.) It only has 14,400 miles on it, since it was only used locally. After meticulous restoration, it is the pride and joy of the Museum!

The Telecruiser was used by WFAA Dallas and the ABC network for coverage of the aftermath of the Kennedy assassination in November 1963. And, the actual TV camera that broadcast the horrific moment when Jack Ruby shot Lee Harvey Oswald is also among the Museum’s camera collection.

Color TV

It wasn’t until the mid 1960s that color TV sets started selling in large numbers. In 1965 it was announced that over half of all network prime-time programming would be broadcast in color.

In most major cities, the “big three” networks (ABC, CBS & NBC) all had local affiliates, and by the late 60s PBS joined the lineup, along with a UHF station or two.

Cable TV

Cable TV began as a replacement for over-the-air TV programming in some rural areas and in mountainous cities, where the terrain created a challenge for TV reception. In 1948, cable services providing broadcast TV channels were installed in Arkansas, Oregon and Pennsylvania. Things changed as the 1980s approached, and cable posed a viable threat to the networks. In 1979, ESPN became the first 24-hour cable network.

Advancements in video technology, bandwidth, and improvements in digital TV created an avalanche of demand for consumer Cable TV in the 1990s. That decade began with 57% of U.S. TV households and 79 TV networks on cable. At that time, decent quality video on the Internet was practically nonexistent, since the Internet was accessible primarily through very slow telephone dial-up connections.

By 2012, 93% of American households had access to cable broadband, which – importantly – now included the Internet! This means that cable’s looming competitor, high-speed broadband Internet with High Definition streaming video and video-on-demand, was now part of the package from your cable company.

While traditional cable TV and the original “big three” networks are still a driving force, every TV content provider has diversified into new distribution technologies. High-speed fiber optic networks are now gaining market share.

BOTTOM LINE:

The future of audio and video recording and broadcasting is here and now and ever expanding. Wireless and on-demand content are expected to eclipse legacy delivery methods. And with a plethora of Social Media options, including Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, Youtube, TikTok and many more, literally at your fingertips, you are now a part of it all.

Just think: for the past 100+ years, everything that all those inventors and technicians created and pushed forward has led up to today’s means of content and distribution. You don’t need a lucky break from a TV network or a record company to put your creativity in front of an international audience. With the Internet the pipeline is there for you to create and promote your skills and wares.

You are the future of audio and video broadcasting – which means its history is your history! Enjoy!

AND BEFORE WE SIGN OFF . . .

The Texas Museum of Broadcasting & Communications has other fascinating legacy items on display, such as 35mm carbon-arc movie projectors, a complete TV news set, several radio studios, and a Showco audio mixing board designed specifically for James Taylor’s 1973 tour – and subsequently used by Paul McCartney, the Rolling Stones, Jackson Browne and Linda Ronstadt!

They also have a vintage telephone switchboard, and even a tube tester!

Studio 4, their banquet area, can accommodate 200 to 300 seated guests and is available for event rental.

The Texas Museum of Broadcasting & Communications is located at 416 E. Main St. Kilgore, Texas 75662.

Currently their hours are 10 AM to 5 PM on Fridays and Saturdays; groups by appointment. The Museum also hosts the Texas Radio Hall of Fame.

A visit to Kilgore should also include the East Texas Oil Museum.

Sign up to get more articles. It’s free:

One thought on “Cool Vibes At the Texas Broadcast Museum In Kilgore”