Bourbon Street in the French Quarter of New Orleans; image courtesy Lars Plougmann

“Laissez les bon temps rouler!” with Pirate Jean Lafitte

By Ria Nicholas

The city of New Orleans has seen a lot of history since its founding in 1718. But it is, perhaps, the nefarious pirate Jean Lafitte who has left the most indelible mark upon the Crescent City. Whether that mark be for better or worse, I will leave to your judgment. Here are 10 destinations he may have “touched” . . .

. . . and the wild history behind it all, for those who crave a little more.

1. Lafitte’s Blacksmith Shop

At the corner of Bourbon Street and St. Philip, in the old-worldly French Quarter, squats an ancient brick and plaster structure known as Lafitte’s Blacksmith Shop Bar.

Subscribe to more articles. It’s free:

Was this establishment, in fact, frequented by the infamous pirate Jean Lafitte? The Blacksmith Shop was owned, at the time, by the family of a record-shy “entrepreneur” and a privateer reputed to command a ship in Lafitte’s fleet. The building would have served as a logical front for illicit smuggling negotiations. The present owners describe the legend as “a gumbo of truth.” But the mere possibility of a clandestine connection sparks our imagination and feeds our obsession with the darker side of humanity.

Built sometime in the early 1700s, Lafitte’s Blacksmith Shop is said to be the oldest structure used as a bar in the United States. This intimate pub famously – and appropriately – serves “hurricanes*” and “voodoo daiquiris,” among other libations. Lafitte’s Blacksmith Shop also acts as a popular piano bar, supplying live entertainment.

* The “Hurricane” cocktail was invented at Pat O’Brien’s, also a New Orleans staple.

JEAN LAFITTE – THE BEGINNING: No one knows exactly when or where Jean Lafitte was born. He seems to have arrived this side of hell sometime around 1780, a number of years after the Blacksmith Shop was built. And, depending on how much credibility you want to assign to various experts and documents, you may choose from among several likely birthplaces, including: Bordeaux, France; Orduña, Spain; and Westchester, New York. To me, the French colony of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) seems the most probable candidate.

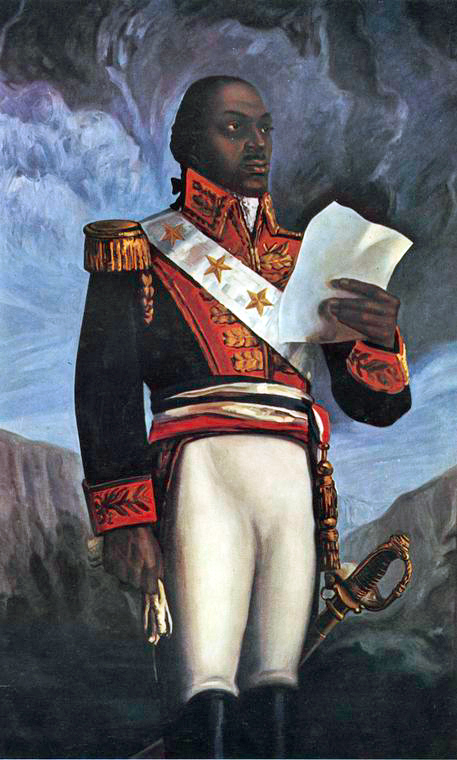

His childhood, if ever he had one, remains equally obscure. Perhaps he spent it on Saint-Domingue or in New Orleans or mostly aboard ships owned by his father, a trader. If he grew up on Saint-Domingue, he may have escaped to New Orleans as a result of the Haitian Revolution. (Haiti was the second colony in the “New World” to gain its independence, as a slave revolt there overthrew the French regime.)

We do know that, beginning roughly in 1805, Jean and his older brother Pierre were running a thriving “import business” out of a warehouse in New Orleans.

To put into context the subsequent crimes and misdemeanors that defined Lafitte’s life, we have to appreciate the fluid and tumultuous times in which he pursued his vocation:

1791 – 1804: the Haitian Revolution (Saint-Domingue)

1803 – 1815: the Napoleonic Wars (Various European coalitions battle each other and intercept American trade.)

1812 – 1815: the War of 1812 (U.S. vs. Britain – a/k/a “American Revolution, part II”)

1810 – 1821: the Mexican War of Independence

2. Marie Laveau’s House of Voodoo

This post is brought to you by RiaNicholasDesigns.com

Marie Laveau’s House of Voodoo accommodates a spiritual shop and museum in the building once occupied by the “Second Queen of Voodoo” (b. 1827; d. ~1895). She and her mother, the “First Queen of Voodoo,” Marie Laveau (1794–1881), exercised great influence over their followers. New Orleans Voodoo, a blend of West African rituals and Catholicism, was largely imported into New Orleans with the slave trade and by followers fleeing the Haitian Revolution. Marie Laveau’s offers a variety of gifts and apparel, as well as psychic readings and more. Jean Lafitte, though older, was a contemporary of Marie Laveau, was a slave trader and smuggler operating out of New Orleans, and was possibly born and raised on Saint-Domingue. He was probably passingly familiar with the rituals of voodoo.

Sign up for more articles. It’s free:

Image is in the public domain.

THE NAPOLEONIC WARS: As the Lafitte business was gearing up in New Orleans, so were the Napoleonic Wars in Europe. With Britain and France embroiled in a bitter clash overseas, both of their navies began targeting neutral American merchant ships in order to disrupt each others’ trade. They routinely seized American cargo as “contraband,” accusing American merchant marines of trading with “enemy nations.”

Additionally, the Brits made a nasty habit of impressing American sailors into their Royal Navy. Between 1793 and 1812, the British kidnapped more than 15,000 American citizens and forced them to fight for England in their ongoing European wars.

In 1807 Congress responded to these naval threats by enacting a law (the “Embargo Act”), which barred American ships from docking at any foreign port and imposed an embargo on all goods imported into the United States.

In other words, the United States shot itself in the proverbial foot! While this Act had virtually no effect on England or France, the Embargo Act devastated the U.S. shipping industry and threatened to bankrupt American merchants who depended on international trade. The Embargo Act also inadvertently brought about a positive public attitude toward smuggling.

3. Royal Street

From the beginning, Royal Street’s proximity to the Mississippi River docks made it a likely center for trade and commerce, and it is quite possible, even probable, that Jean Lafitte delivered smuggled goods to merchants who operated here. Today, this upscale thoroughfare, which stretches from Canal Street to Esplanade Avenue, is lined with exclusive salons, antique shops, and art galleries. Fine imports and hand-crafted furniture vie for attention with rare coins, fine jewelry, and historic memorabilia.

was acquired by the U.S. in 1803

BARATARIAN BUCCANEERS: Ever the opportunist, Lafitte structured his “import business” around the Embargo Act! In fact, Jean and his brother made an art form out of smuggling foreign goods into New Orleans.

First, with the U.S. growing more serious about enforcing the Embargo, Lafitte moved his operation from the newly American (formerly French – then Spanish – then French) city of New Orleans to Barataria, one of an isolated smattering of sea-level islands dotting the coastal marshes along the Mississippi Delta.

This was his scheme: Lafitte carried legal (domestic) goods into New Orleans and returned to Barataria with supplies. However, he didn’t list those supplies on his ship’s manifest during the return trip. Instead, he listed illegal contraband he had stored at Barataria. (He knew that customs agents were only concerned about goods being smuggled into the country. They didn’t bother to read ship’s manifests of goods coming out of New Orleans. They routinely signed and approved those manifests.) Now that the false manifest was signed and approved, Lafitte could use it to “legally” bring the contraband into New Orleans.

4. The French Market / Café du Monde

The French Market dates back to a time when Native Americans met on the natural levee of the Mississippi River to trade their wares. When New Orleans was settled by Europeans, its original trading posts were open air markets. The first French Market building was constructed in 1771 but destroyed by a hurricane in 1812. The following year it was replaced by the structure which now houses Café du Monde. The building was originally a meat market. It is conceivable that Lafitte purchased some of his supplies for Barataria there. In 1822, a vegetable market was added. More shops were built in 1833, and over the years, various agencies have made renovations, additions, and improvements to the market. Today, the French Market is a thriving, bustling center for commerce.

Café du Monde was established in 1862, well after Jean Lafitte’s death, in the French Market’s old meat market building. With its world-famous Beignets and Café au Lait, it is THE place for a leisurely cup of coffee, dessert, and people watching. Just be prepared to wait in line, since it can get quite crowded during busy times.

By 1810, Lafitte had grown his smuggling venture into a profitable success.

5. Bourbon Street

Just a block from Royal Street, Bourbon Street, too, stretches through 13 blocks of the French Quarter, from Canal Street to Esplanade Avenue. But if Royal Street is the epicenter of upscale shopping, then Bourbon Street is the place to “laissez les bons temps rouler!” (Let the good times roll!)

The street dates back to the founding of New Orleans in 1718 and was named for the then-ruling Bourbon family of France, not for the liquor so often consumed there. (Perhaps Lafitte hoisted a tankard or two to his success on Bourbon Street?) Like much of the rest of the French Quarter, Bourbon Street’s architecture dates to a time after the Great New Orleans Fire of 1788. At this time, the city was a Spanish colony and was rebuilt in a Spanish style. In addition to New Orleans’ world-famous Mardi Gras celebrations, usually held after Epiphany and culminating the day before Ash Wednesday, visitors here may find a number of year-round entertainment options, including restaurants, pubs and jazz clubs, and a vibrant LGBT nightlife scene past the “Lavender Line,” where St. Ann Street crosses Bourbon.

6. The Old Absinthe House

In addition to Jean Lafitte’s Blacksmith Shop, you will find the Old Absinthe House, (240 Bourbon St.) built in 1806 as a family-owned importing firm, on Bourbon Street. The second floor of the structure is rumored to have been the meeting place where Jean Lafitte and General Andrew Jackson negotiated for the pirate’s support in the Battle of New Orleans. (More on that below.) In 1815, the ground floor was converted into a saloon. Later, in 1874, mixologist Cayetano Ferrer created his famous Absinthe House Frappe here. You can still order the beverage in the same ground floor saloon today.

7. Maison Bourbon

photo by Ria Nicholas

Maison Bourbon was built circa 1799 at the corner of Bourbon and St. Peter Streets, and it is likely that Lafitte passed by the building on his trips into New Orleans. Today, Maison Bourbon houses one of the Quarter’s oldest live jazz clubs and prides itself on preserving “America’s music” in the tradition of Louis Armstrong. Harry Connick, Jr. got his start here.

THE PIRATE LAFITTE: Emboldened by success, and apparently desirous of a bigger cut of the action, Lafitte expanded his smuggling enterprise to include piracy.

Sign up for more articles. It’s free:

In 1812, Lafitte purchased a schooner and hired a captain to support his acquisition of goods. The schooner soon seized a brigantine and its cargo and began adding to Lafitte’s growing fleet and ill-gotten inventory.

A substantial portion of Lafitte’s “business,” both in New Orleans and later on Galveston Island*, involved the slave trade. In 1807, the United States passed a law forbidding the import of slaves – though, tragically and illogically, not the possession or domestic trading of slaves. The law, which established fines and prison sentences for anyone caught in the international slave trade, also contained a loophole diabolically suited to Lafitte’s self-serving enterprises.

Rather than freeing illegally imported slaves – either in the U.S. or back in Africa – the law provided that they would be sold on the American slave market, the profits inuring to the state where they were sold. Moreover – and here is where Lafitte saw his opportunity – naval ships that seized such illegal “cargo” would share in the proceeds of their sale.

This was his scheme: Lafitte would capture foreign slave ships, take the slaves to New Orleans and turn them over to U.S. Customs. His representative (a straw man) would then purchase them at auction. Lafitte would collect half the proceeds of the sale – his legal finders fee. He would then own the slaves legally and resell them at full price on the slave market, pocketing a handsome profit. (If my explanation of the process sounds cold and calculating, then I have done my job well. Empathy and Compassion never attended slave auctions.)

* For a list of fun, historical destinations in Galveston, see our article titled “12 Galveston Time Capsule Adventures.”

8. Pirate’s Alley

A narrow 600-foot alleyway, running between St. Louis Cathedral and the Cabildo goes by the intriguing name “Pirate’s Alley.” Legend holds that Jean Lafitte conducted business meetings in its shadows – though this is unlikely, considering the proximity of the local jail. Here you can visit the house where William Faulkner penned his first novel, Soldiers’ Pay. The Alley is also home to the “lab” where Momus Alexander Morgus “the Great” created his “Mad Scientist” sketches, which served as lead-ins to corny vintage science fiction and horror movies. Finally, Pirate’s Alley acts as a popular, if atypical, wedding venue.

THE WAR OF 1812: In light of the dismal failure of the Embargo Act and the ongoing British practice of kidnapping Americans, President James Madison eventually declared war on Great Britain, the mightiest naval power in the world.

Within two years, with the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo in 1814, Britain was able to turn all of its resources against the United States. Britain soon successfully blockaded ports up and down the eastern seaboard and the Gulf of Mexico, crushing the U.S. economy.

In August of that year, British forces marched on Washington, D.C., captured the city, and burned the White House (then called the Presidential Mansion), the Capitol, and most other government buildings. Apparently, utter destruction of the Capitol was only averted by a torrential rain storm.

At about this time, an English ship arrived at Barataria, bearing a persuasive letter, addressed to Jean Lafitte, from none other than King George III. The letter offered Lafitte and his men British citizenship and lands in the British colonies – on two conditions:

- 1. Lafitte was to return all Spanish ships he had seized to Spain, currently Britain’s ally; and

- 2. Lafitte would agree to use his ample resources to assist Great Britain in winning the war against the U.S.

Britain’s plan was to capture New Orleans, then move up the Mississippi River, and, in concert with British forces in Canada*, “shove the Americans into the Atlantic Ocean.”

If Lafitte refused, the letter warned, the Royal Navy had orders to capture Barataria and put an end to the smuggling.

Lafitte weighed his options and chose to side with the United States.

* Find suggestions for a variety of things to do at Put-In-Bay, Ohio on Lake Erie – and a little history behind America’s response to British forces there during the War of 1812 – in our article titled “Sun, Fun, and the Battle We Won At Put-In-Bay, Ohio!“

9. Napoleon House

Napoleon House, at the corner of Chartres and St. Louis Streets, is the former home and business of Nicolas Girod, mayor of New Orleans. He was instrumental in raising a militia – including Jean Lafitte and his men – to help General Andrew Jackson defend the city during the Battle of New Orleans. The House derives its name from the legend that Girod and Lafitte conspired to smuggle Napoleon Bonaparte here from his exile. Built in 1794 and expanded to its current size circa 1815, it currently houses a popular restaurant know for its Muffuletta sandwiches. You might also recognize Napoleon House from its cameo appearances in movies such as “JFK,” “Runaway Jury,” and “Earthbound.”

In December of 1814, the Royal Navy launched its attack on New Orleans.

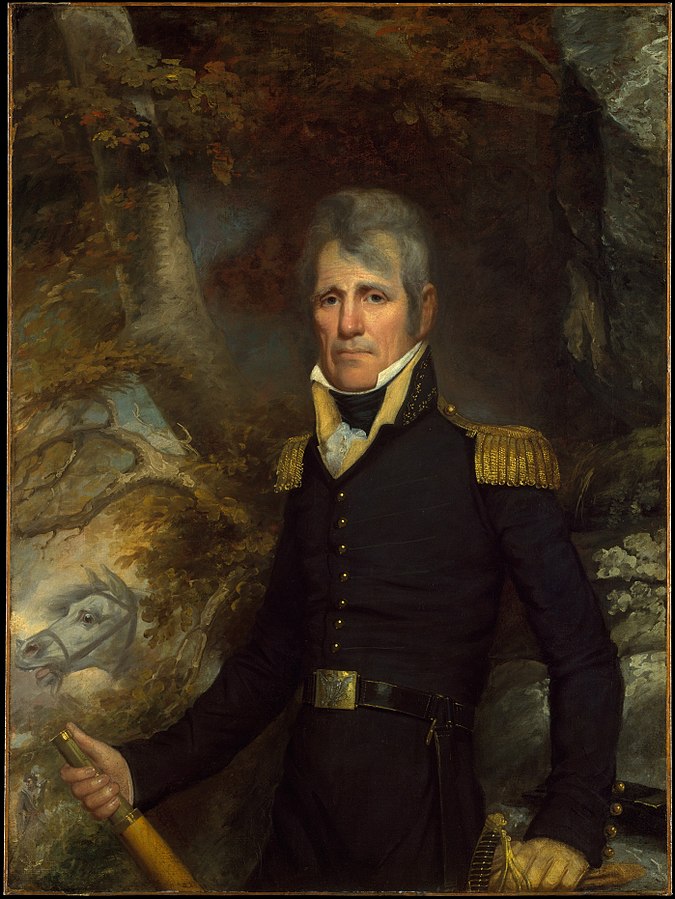

OLD HICKORY AND THE HELLISH BANDIT: Major General Andrew Jackson rushed to the defense of the city, and Jean Lafitte volunteered to assist him. By 1814, Lafitte and his privateers – about 1,000 of them – had amassed a fleet of more than 100 vessels.

“I ask you, Louisianans, can we place any confidence in the honor of men who have courted an alliance with pirates and robbers?”

— General Andrew Jackson

Jackson, whose nickname, “Old Hickory,” implies that he was as tough and shrewd as Lafitte, expressed skepticism at the offer. But he literally needed all hands on deck at the Battle of New Orleans.

Lafitte and the Baratarians had massive amounts of gunpowder and munitions squirreled away in the swamps. Moreover, they knew how to maneuver ships and man artillery. And they were familiar with the maze of barrier islands and salt-grass marshes of the Delta. Lafitte, whom Jackson originally described as a “hellish bandit,” proved so valuable during the ensuing battle that he became Jackson’s unofficial aid-de-camp.

On January 8, 1815, Jackson, with his relatively small ragtag militia of pirates, frontiersmen, free blacks, and Choctaw Indians, repelled a force of 8,000 trained British troops at the Battle of New Orleans. (Both sides were unaware that a peace treaty had been signed at Ghent, Belgium only days before.)

10. Jackson Square:

- St. Louis Cathedral,

- the Cabildo, and

- the Presbytère

Originally called “Place d’Armes,” NOLA’s Jackson Square bears the name of Andrew Jackson*, in recognition and appreciation of his leadership during the Battle of New Orleans.

The Square sits directly in front of the St. Louis Cathedral and dates back to 1721. Designed after the traditional squares in Paris, its proximity to the Mississippi River made it an ideal open-air market place and military parade ground. Today, the Square draws artists and street performers. The church distinguishes itself as the oldest cathedral in continual use in the United States.

* At the time of this writing, there is a push to remove the statue of General Jackson from Jackson Square. Proponents of the removal cite the fact that Andrew Jackson was a strong supporter of slavery and profited greatly by the institution. He personally owned and traded as many 160 slaves and was known to treat them harshly. He was also an anti-abolitionist, intercepting anti-slavery literature and referring to abolitionists as people who should “atone for this wicked attempt with their lives.” Additionally, President Jackson was a vigorous proponent of westward expansion, including the forcible removal of Native Americans from their lands. Policies he supported resulted in the “Trail of Tears,” as well as untold loss of lives and the virtual obliteration of Native cultures.

Built between 1795 and 1799, the Cabildo houses the site where the Louisiana Purchase transfer was ratified in 1803. It was the seat of New Orleans’ government until 1853, when it became the location of the Louisiana State Supreme Court. Today, it contains the Louisiana State Museum, featuring a comprehensive exhibit on Louisiana’s early history.

The Presbytère, built from 1791 to 1813, matches the Cabildo but flanks St. Louis Cathedral on the opposite side. Originally intended to house clergy, it was never employed for that purpose. Instead, it operated as a commercial building until 1834, when it started serving as the Louisiana Supreme Court building. Today, it comprises part of the Louisiana State Museum with two permanent exhibits: “Mardi Gras: It’s Carnival Time in Louisiana” and “Living with Hurricanes: Katrina and Beyond.” Certainly Jean Lafitte would have crossed Jackson Square many times and been familiar with these buildings during his time in New Orleans.

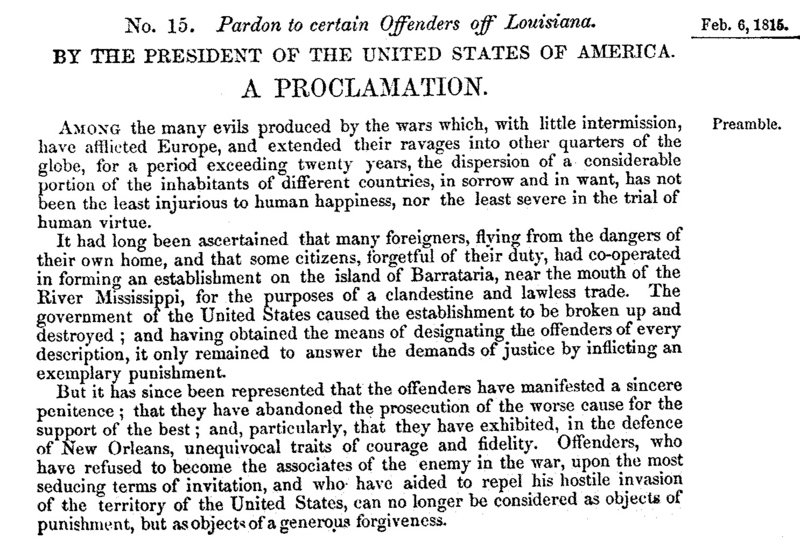

For his part in defending the United States, Lafitte received a full presidential pardon from President James Madison and . . . promptly resumed his chosen career.

PIRATE TO THE END: In 1816, the Lafitte brothers signed on as spies for Spain during the Mexican War for Independence, and Jean Lafitte relocated to Galveston Island* in Spanish Texas. Shortly after his arrival, the revolutionaries left the island, and Lafitte established a pirate camp he called Campeche. Controlled from Maison Rouge, Lafitte’s two-story, red-painted headquarters, his Galveston Island colony grew to more than 120 separate structures and over 2,000 residents. At the height of its success, it took in millions of dollars annually from stolen and smuggled goods and slaves.

Please visit our article titled “12 Galveston Time Capsule Adventures” to learn more about travel destinations on historic Galveston Island!

Lafitte’s stay on Galveston lasted a brief three years before hostilities with local Karankawa Indians, the ravages of a hurricane, and a further assault from the U.S. Navy ousted him. He ordered the remaining structures of his camp burned to the ground and left.

A couple of years later, he was mortally wounded when, through a fatal miscalculation, he engaged in a skirmish with a heavily armed ship off the coast of Central America.

Lafitte was wickedly intelligent, diabolically creative, viciously cunning, and brutally bold. We must be on guard against idolizing him! We must never forget that he was also fickle, self-serving, and inhumane, with loyalties that shifted capriciously with the winds of his own fortune. He was a consummate schemer, scammer, slaver, and smuggler. And, to the very last, he was a pirate!

Travel Tips

Accommodations:

New Orleans’ French Quarter provides many hotel choices, including familiar brands such as Best Western, Omni, Hyatt, and Ritz-Carlton, as well as boutique hotels, such as the Andrew Jackson Hotel at 919 Royal Street. Alternatively, you could choose from a variety of vacation rental options. There is literally an accommodation for every budget.

The French Quarter also offers many outstanding restaurants and bars in addition to the ones covered in this article. One I feel compelled to recommend, though it didn’t fit under the ‘umbrella’ of the Lafitte story, is Pat O’Brien’s at 718 St. Peter, New Orleans, LA 70116. Its Courtyard Restaurant with flaming fountain is connected to the bar where the hurricane cocktail was invented.

Of course there’s more – too much for me to cover in one post. The area beckons you to explore on foot to discover its many hidden treasures. Countless additional attractions, both historic and modern, await you around every corner. We would love to hear from you about your favorite culinary and entertainment experiences in the French Quarter!

Weather:

A warm climate dominates New Orleans, with average temperatures ranging from a low of 47°F (8.33°C) in January to a high of 92°F (33.33°C) in July and August, although it can get hotter or colder. Summers can feel oppressively hot, with humidity hovering near 100%. Average rainfall is also highest during the summer months, June – September. Hurricane season lasts from June 1st to November 30th, and New Orleans experiences its fair share, so keep an eye on weather forecasts when planning your trip.

Safety:

While the French Quarter is considered generally safe (not totally safe), several surrounding areas have higher violent crime rates. When walking, especially at night, it is best not to stray from the French Quarter. And when indulging in adult beverages, make sure you are still able to keep track of your personal belongings.

Sign up for more articles. It’s free:

3 thoughts on “Tour the French Quarter With NOLA’s Original Bad Boy!”